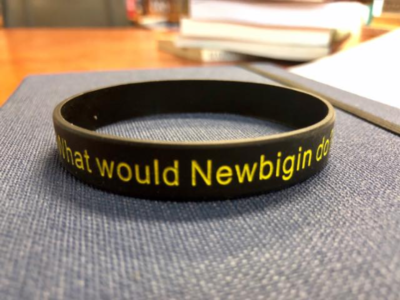

The Lasting Legacy of Lesslie Newbigin

Like many others, I can’t seem to get enough of Lesslie Newbigin. Ever since reading The Gospel in a Pluralist Society and Foolishness to the Greeks back in the early 90’s, I have an insatiable appetite to revisit his writings over and over again. From a missiological perspective, Newbigin is arguably just as relevant to the church today as he was when he first began to speak so prophetically to the Western Church in the 70’s. His non-colonial, dialogical sowing of the gospel in the cultural soil of India still offers us a pattern for cross-cultural immersion everywhere – even in our local neighborhoods. Recently I found the following little tribute to Lesslie Newbigin put together by author/professor Michael Goheen. It is well worth dwelling upon.

“Duke University theologian Geoffrey Wainwright said that when the history of the 20th century church is written, Lesslie Newbigin (1909-1998) will be among the top 10 or 12 theological thinkers of the century. Newbigin spent forty years in India as a missionary. Upon his return to England in 1974, he published numerous books and began to command an international audience. His missionary eyes brought fresh sight to the Western church as he called for a missionary encounter with Western culture. And it is in that phrase—a ‘missionary encounter with Western culture’—that we find Newbigin’s enduring legacy for the Western church today.

A missionary encounter, for Newbigin, involves the recovery of three things: the public truth of the gospel, the missional nature of the church, and a missional analysis of Western culture. The word ‘recover’ is carefully chosen—it assumes that these things have been lost in our history.

According to Newbigin, the public truth of the gospel has been reduced to a personal message about the otherworldly future of the individual person. He believed, however, that the gospel is a message about the goal of cosmic history. In the death of Jesus God dealt with the evil of the whole world, and in his resurrection the renewing power of a renewed creation broke into history. This restored creation will one-day fill the whole earth and all of history will culminate in the kingdom of God. If this is true, Newbigin argues, the Gospel is not a private message. It is news about the goal of universal history, the cosmic completion of God’s purpose to restore his original creational intentions for the whole creation and all of human life.

Consequently the “Bible tells a story that is the story, the story of which our human life is a part,” says Newbigin, and it is possible for us to know this true story because in Jesus God has decisively and finally revealed and accomplished where the history of the world and humankind is going. And so it is only this story that can give true meaning to the full spectrum of human life today.

If the gospel is true, if it tells us where all of history is going, then mission must follow; the true goal and meaning of universal history has been revealed and now must be made known. The way Jesus chose to do that was not to write a book, as Mohammed did, but rather to choose a community that would make it known by embodying it in its life, expressing it in its deeds, and announcing it in its words. He commissioned them with these words: “As the Father has sent me, I am sending you” (John 20:21). The church is missional by its very nature—a people charged with embodying the true end of history for the sake of the world.

Yet, the mission of God’s people is undermined when it is compromised by cultural idolatry. Newbigin believed that this is exactly what happened to the Western church; it is an “advanced case of syncretism.” A missionary encounter requires that the church embody its comprehensive story over against the cultural story. This encounter is eclipsed when the church allows its story to be accommodated into the cultural story. Thus, it is necessary to analyze Western culture and understand its religious foundation.

Newbigin wrote that “incomparably the most urgent missionary task for the next few decades is . . . to probe behind the unquestioned assumptions of modernity and uncover the hidden credo which supports them.” He quotes a Chinese proverb: “If you want to know about water don’t ask a fish.” Western Christians are unaware of the religious beliefs of their culture because they are swimming in it all the time. They are too easily seduced by the myths of a Christian culture or of a neutral secular or pluralistic culture. Western culture, however, is neither Christian nor neutral—it is shaped by a false religious credo.

So, it is necessary, by way of a missional analysis, to uncover this religious credo. A further problem for most Western people, including Christians, is that the word ‘religion’ describes a department of life concerned with such things as worship, prayer, reading sacred scriptures, an ethical system, beliefs about God and the afterlife, and so forth. Newbigin is impatient with this narrow understanding. Religion is much more basic and comprehensive than that. It is a peculiarity of Western culture to isolate the domain of religion from the rest of life. Religion, he said, is a “set of beliefs, experiences, and practices that seek to grasp and express the ultimate nature of things, that which gives shape and meaning to life, that which claims final loyalty.” Thus religion includes the comprehensive worldviews that shape Western culture, like the modern scientific worldview in both its Marxist and its liberal-democratic-capitalist expressions. If the Western church is to be faithful to the gospel and its mission, we will need to work hard to understand the religious beliefs of our culture in order to extricate ourselves from idolatry.

This will be Newbigin’s lasting legacy—calling the Western church to recover the comprehensive scope of the gospel and its story, its missional identity to embody that story, and a critical stance toward the idolatry of its cultural story. And, perhaps, the life of the Western church will depend on owning Newbigin’s legacy.”