Coaching Startup Teams toward an Inclusive Missional Ecclesiology

“The traditional church makes it quite difficult for people to negotiate its maze of cultural, theological, and social barriers in order to get “in.”.. and by the time newcomers have scaled the fences built around the church, they are so socialized as churchgoers that they are not likely to be able to maintain their connection with the social groupings they came from. So we lose contact with non-believers and we lose the ability to relate to them. We extract people from their natural habitats and substitute “attractional” and “come-to” structures for missional life.” – Leonard Hjalmarson 1

Centered Sets & Bounded Sets

One of the biggest challenges church planters face is how to operate as a covenant community that not only makes room for those outside the forming church but also for those who are closer-in and interested though not ready to commit to Christ and/or the emerging church. Are there ways to include and value all people connected to the church plant (both non-Christians and interested Christians), in the hope that they too may one day want to make a solemn, discerned commitment to the new community, and if appropriate, Christ too?

I believe a “centered set approach” is one way planting teams might effectively hold these two aspects of committed covenant community and inclusiveness in healthy tension. I mention this in a coach training, as I find this approach can radically elevate church planting effectiveness in terms of both evangelism and cooperative shalom-sowing with non-Christians. We as coaches are not responsible to equip starters in this way of operating, of course, but it can be greatly helpful to a project if we ourselves have some sense of how to coach toward activating it.

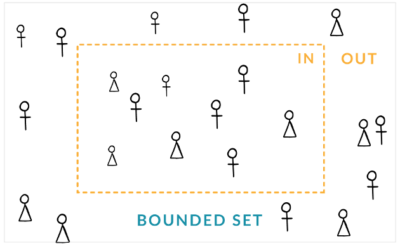

Missiologist Paul Hiebert first articulated the centered set idea in Christian circles. Hiebert identified two primary categories through which we might view belonging to a group: 1) “bounded set” thinking; and 2) “centered set” thinking. A bounded set (as applied to ecclesiology) would be a group that, by their unified commitment around a set of characteristics, beliefs and behaviors, defines clear boundaries on who is “in” and who is “out.” As such, it is based on location and is thereby static – you’re either inside the circle, or you’re not. The following diagram (figure 3) depicts a bounded set approach, which emphasizes getting people into the forming church community as the primary goal, rather than finding ways to integrate anyone who is moving toward love or the shalom reign of God.

– Figure 3 –

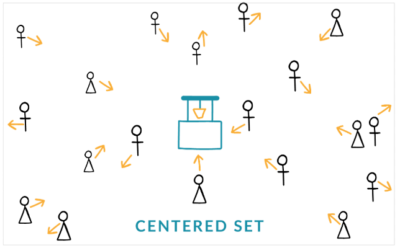

A centered set, by contrast, is defined by its center or its desired destination. It is based on direction – a person is either moving toward or away from the center. In this discussion, the center or destination would be God, or from the vantage point of one still awakening, love or wholeness or whatever conception they hold of the highest ideal toward which they’re living. In contrast to bounded sets, centered sets are dynamic and inclusive. In contrast to the bounded set way of operating, the following diagram (figure 4) captures a centered set approach.

– Figure 4 –

Bounded sets, when existing apart from centered sets, focus on boundaries which must be policed to insure the right people are in. Those not qualifying are clearly seen as outsiders. With centered set thinking, the only boundaries are directional. Either a person is moving toward God or love or goodness, or they’re moving away from that Center or Destination. We don’t categorize those moving toward versus those moving away, but those moving toward God or love or goodness will find much more grounds for relational connectedness and solidarity with a forming Christ-centered community. Hiebert contended that people in Western culture tend to build their world on the basis of bounded sets, while the worldview of Scripture is based primarily on a centered set approach to reality. 2

A Blended Set – Covenant Community AND Inclusivity

Taking the lead from modern missiologists like Alan Hirsch, Michael Frost, Alan Roxborough and others, I’m contending that churches and church plants ought to practice a blended set approach that sets bounded sets within a wider centered set approach. This blending involves a covenant people who operate in their context as a permeable bounded set, but who also recognize that they steward a wider centered set reality within the constellation of their forming spiritual community. The covenant community maintains the integrity of its UP-IN-OUT commitment framework (discipling pattern), but always sees itself as pursuant of a deeper relationship with God in the alluring light of God’s new creation reign coming. In that sense, the covenant community always operates within a broader centered set approach.

In the Gospels we see Jesus employing both a centered set approach and a bounded set approach simultaneously, challenging the diverse groups he encountered in his journeys with an invitation to deeper commitment. As missiologist, Leonard Hjalmarson, once put it:

The group following Jesus were really a “centered set,” a diverse group at various stages of belief, as well as a core group who were deeply committed to him and his mission. We see Jesus challenging the group, to hear him and believe him, but also to follow him — to take up their cross, to live in a new way, to imitate his life and proclaim the good news. So it seems that Jesus is trying to work with both a centered set and a bounded set. He wants to create a covenant community within the bounded set. 3

In like manner, Alan Hirsch and Michael Frost make the claim: “Jesus’ faith community was clearly a centered set, with him at the center…It seems that the community of Christ was not as simple as thirteen guys roaming the countryside. There was a rich intersection of relationships with some nearer the center and others further away, but all invited to join in the kingdom-building enterprise.” 4 Hirsch and Frost, in their book The Shaping of Things to Come, frame Hiebert’s original ideas in a less abstract manner, using the language of “wells and fences” (appropriate for missiologists from the land of Oz). Their explanation goes something like this. 5

In parts of the Australian outback, ranchers do not need to construct fences to keep cattle in. If they dig a well and it’s the only source of life-giving water in the area, the cattle will self-police their wandering and generally stay within reach of the water. In like manner, people in the constellation of a church plant who are in process, or who are seeking or otherwise anxious about committing, will tend to keep moving along with the herd as long as that movement is toward life.

Given that the call of a missional church is to be a pilgrim people in the world, there is no need to erect a special covenant membership fence that keeps people out. Nonmembers should be welcomed to walk alongside and within as fellow practitioners of the Jesus-life, allowing them to “taste and see that the Lord is good” as they freely participate in aspects of the forming community’s life. And, in a reciprocal sense, covenant community members should welcome invitations by those not walking in that covenanting to co-participate in aspects of shalom-activation beyond the forming church’s self-generated practices and activities.

This open, inviting stance, however, does not preclude people being able to commit themselves meaningfully and significantly both to Jesus and to the new expression of his body. There are still some fences involved. The fences, however, are not meant to keep people out. They are there to guard and foster the community’s integrity, sustainability and unique identity. These boundaries mark out what the church holds as non-negotiables for those who agree or covenant to shoulder the community as their own.

Included in these boundaries is a relatively fixed field of theology, direction and values, and often plants eventually include an explicit agreement on expectations (that may be revisited occasionally). Again, unlike those fences on the Australian outback, the ones described here are permeable. They allow those not yet ready to commit the opportunity to also participate on some level in the life of the community, to run with the herd, if you will. A no-strings attached participatory situation is enabled that allows people to both belong before they believe and also to behave (practice some of the forming church’s rhythm of life) before they believe. 6 At the same time, people can commit (or covenant with the community) to formally belong by agreeing and supporting the church’s vision, values, doctrine, rhythm of life, etc.

Belonging in a covenantal way with others, with mutual promises of support on both sides – member to new church, new church to member – strengthens both the overall centered set community as well as the individuals in the covenanting group. And it frees the ones committing to communally uphold one another as they endure the burdens and share in the joys of those who are not ready or able to join the emerging church as fully vested, covenanting members. At the same time, this formal bounded set belonging remains inclusive of those in process, encouraging these people to hang with the community and try on its beliefs and way of life in the hope that they too will want to eventually join in as covenanting stakeholders committed to one another’s fruitful apprenticeship to Jesus.

To illustrate how this blended bounded-set within a centered set approach works in real life, here’s a story of how one Canadian blogger moved from a generic belief in God toward faith in Christ:

“When I first committed to nurturing my relationship with God, my top priority was finding a community to belong to. I was beginning to trust in God, but I did not have any specific beliefs about Jesus, and was skeptical of Christianity in general (as many in my generation are). Fortunately, I found a Quaker community that was able to love and accept me as I was. Though I had lots of hang-ups, and my theology was still a jumbled mess, they were patient with me and did not jump in to correct me. Instead, my newfound community encouraged me to study the Quaker tradition, and to dedicate myself to the practices of waiting worship, discernment and personal prayer.

These practices were a gateway for me into discovering the intellectual contours of my faith. As I waited in the silence, studied the tradition, learned to pray and began to read the Scriptures, my life began to change – and so did my ideas about God! I started learning about who Jesus is, allowing him to speak to me through the Scriptures and through his Spirit. No one was forcing me to adopt a party line, yet as I continued to engage in prayer and study, I found myself growing into a deeper appreciation for orthodox Christian faith.

…For me the traditional pattern was reversed: Instead of “believing, behaving, belonging,” I first found belonging in a supportive spiritual community. There, I learned practices that taught me how to “behave.” Finally, this supportive community and the spiritual practices they taught me drew me into an authentic set of beliefs, grounded in both my own personal experience and in Scripture.” 7

Missiologist Alan Roxburgh notes that “centered-set organizations do not define membership and identity as the entry points or boundaries, whereas bounded-set groups have initiation rites through which prospective members must move before they can join.” 8 Essentially, what Roxburgh is saying this: If one sees the local church as a wider congregation composed of a mixed set of people on a journey toward God or the God-life (with some fully on board and others less so), there is no need to identify who is “in” and who is “out.”

The congregation can have permeable borders where non-Christians and nominal Christians can find places of belonging among the general pilgrim people. Within this larger pilgrim set, and moving in the same general direction, is a “bounded-set” group, meaning it has specific membership criteria. This group operates as a covenant community, or a family of diverse siblings who look out for each other and for the interests of the community to which they are bonded. Roxburgh goes so far as to label them a “secular Order,” which he defines as “people who commit themselves to an ordered, covenant life within the reality of their everyday callings as spouses, children, siblings, workers who live in neighborhoods, and those who work in the larger community.” 9

Like the ancient Celtic Christians, Roxburgh’s covenant community intentionally includes non- Christians in the community’s journey. In other words, the “belonging-before-believing” and “behaving before believing” dynamics I allude to above are enabled. The bounded-set covenant community has a missional ministry among the common journeyers in the overall centered-set congregation and among non-Christians in the spheres of their daily life outside the church.

The covenant community is equipped and sent out into culture, so that everyday missionary living in the workplace, school, neighborhood, and other spheres of life is widely practiced and continually yielding a strong relational interface with non-Christians. Such missional ministry within and without has the hopeful aim of moving non-Christians into an initiation process culminating in baptism and inclusion in the covenant life, practices and accountability of the covenanted people. According to Roxburgh, church and para-church leaders must be equipped to cultivate such covenant communities within local expressions of church. 10

It’s also critically important for us to realize that many nominal or loosely-attached Christians, straying DONE’s (those done with church but not with Jesus), and even non-Christians may claim they belong to our church when asked. This means church planters must be careful not to suggest that the decision about belonging is finally our decision. In other words, belonging exists across a spectrum and ought not to be the determining factor for who has the right to call themselves a member. It’s okay to have generic members, and it’s even better to have covenanted members.

A covenanting or formal agreement process allows planting initiatives to have both kinds of “members” peacefully co-existing. It provides people with a pathway to go deeper in, a pathway to express their sense of belonging in tangible behaviors that strengthen both their discipleship and the relational fiber of the church also. This is where belonging most strongly crosses over to stake-holding or ownership, which is essential if a given planting team hopes to see their local “body of Christ” move in harmony as an embodied expression of the gospel. Without this two-way commitment (person to church; church to person) planters may have a lot of people claiming the church as home, but not nearly as many who are willing to offer themselves to help animate it beyond the rudimentary level of a Sunday worship gathering.

Admittedly, holding covenant community membership in healthy tension with inclusivity of people of all types and varied levels of belonging requires leadership discernment, finesse, and wisdom. But it is well worth the added complexity, as both partners and those not yet desiring such are able to share in and contribute to the ministry and growth of “their” church as well as the sowing of goodness and shalom in the wider host culture. Alan Hirsch contends that this centered-set approach is key to any church claiming to be “missional-incarnational.”

Coaching Church Starters into a Blended Set Approach

So, imagine a pioneering church startup team interacting over the ideas above, and then coming to you as their coach to help them implement it. You do not have to fine-tune their understanding by putting on the mentor hat, but you do truly want to help them excel at both inclusivity and apprenticing people to Jesus. What sort of questions might you employ to help the team move forward in their own way with a blended set approach?

I think it’s helpful for us coaches to generate our own questions, and of course, to flexibly adapt these to the language of a given startup team we’re coaching. I tend to group the questions under two categories: 1) Questions that bolster communal inclusivity and proclamation through cultivating “belonging spaces” and “behaving spaces”; and 2) Questions that relate to helping the covenant community life to be more alluring and accessible as a meaningful commitment.

Coaching questions to foster greater inclusivity and effectiveness in demonstrating/proclaiming the gospel:

- In what ways does your community’s passions and gifts intersect the passions and gifts of not-yet-Christians involved in justice and compassion initiatives in your city?

- How do you envision intentionally creating belonging spaces where your people might have significant ongoing contact with people who’ve yet to say yes to Jesus and/or the Jesus way?

- How might people in the constellation of your community “behave before they believe” (i.e., join you in certain spiritual practices of the forming church)? How might your people participate in justice/compassion practices that local NONE’s and DONE’s are committed to?

- What do you and your team need to do to envision your people in a centered set approach? And what does enacting that inclusive approach look like for you?

- How does your team and community engage in proclamation within inclusivity and co-participation with local culture? What stories of God’s goodness and love do you tell?

- What measures are you taking to “adorn the gospel” (Titus 2:9-10), so that you and your community’s behavior and image, locally, complement the goodness of Jesus?

Coaching questions to help starters embody an alluring and accessible covenant community:

- How might you express your covenant community commitments in positive language that not-yet-Christians can comprehend?

- How do you avoid creating a preferred culture of the committed people versus the floating uncommitted people? (i.e., how do you communicate value to all those awakening in their own ways to God’s goodness, so they don’t feel second rate?).

- What does the process look like for people who want to join the covenant community, whether they be unattached Christians or not-yet-Christians?

- How do you celebrate and honor the relational work of your people in including their non-Christian friends and being involved in good causes outside the church? How do those practices and activities correlate with your covenant community rhythms and practices?

- How important is prayer and an obvious dependance on God to you, and how is that expressed by you and by the covenant community as that pertains to those who’ve yet to surrender to God’s love in Christ?

———————————

Reflecting Exercise – Applying the centered set approach to coaching:

- What advantages to both gospel proclamation and discipleship do you see in a centered set way of operating versus a bounded set way of operating?

- Review pages 59-63 in the book, Dynamic Adventure: A Guide to Starting and Shaping Missional Churches (Centennial, CO: Communitas Int’l, 2017). Imagine how you might coach a planter and their team into creating “belonging spaces” and “behaving spaces” for those outside faith or outside the church. What might that look like specifically?

- How might you encourage a given planter you’re coaching to help not-yet-Christians find their way into a deeper interface with the covenant community (bounded set) the team is cultivating?